Dating of Book of Daniel

This website proves that the Book of Daniel

chapter in the bible was a legitimate prophetic piece of work, written by the

prophet Daniel from the year 570 BC - 536 BC, as traditionally thought. And is

not a fraudulent piece of writing, written sometime between 167 BC to 63 BC as

claimed by critics - In other words written after the world events that the

book of Daniel had prophecised, as critics claim.

It also counters the arguments made by the

critics, who claim that the Book of Daniel is not a prophetic piece of writing,

written from 570 BC - 536 BC, but really a fraudulent piece of writing, written

between 167 BC to 63 BC.

The following text is not my own writing but

credit goes to a free book named: ''Pay Attention to Daniel's prophecy''. However I have slightly edited some bits or

added my own writing, for the purpose of clarity.

1. Proof that the Book of

Daniel was written around 536 BC

Prophet Ezekiel

One of Daniel’s contemporaries was the prophet

Ezekiel (622 BC - 570 BC). He too served as a prophet during the Babylonian

exile. Several times, the book of Ezekiel mentions Daniel by name. (Ezekiel

14:14,20; 28:3) These references show that even during his own lifetime, in the

sixth century BC, Daniel was already well-known as a righteous and a wise man,

worthy of being mentioned alongside God-fearing Noah and Job.

Dead Sea Scrolls

The authenticity of the book of Daniel further

received support when the Dead Sea Scrolls were found in the caves of Qumran,

Israel. Surprisingly numerous among the finds discovered in 1952 are scrolls

and fragments from the book of Daniel. The oldest has been dated to the late

second century BC At that early date, therefore, the book of Daniel was already

well-known and widely respected. The Zondervan Pictorial Encyclopedia of the

Bible notes: "A Maccabean dating (167 BC-63 BC) for Daniel has now to be

abandoned, if only because there could not possibly be a sufficient interval (time)

between the composition (writing) of Daniel and its appearance in the form of

copies in the library of a Maccabean religious sect."

Telling Details

Consider some other details in the book of Daniel

indicating that the writer had firsthand knowledge of the times he wrote about.

Daniel’s familiarity with subtle details about ancient Babylon is compelling

evidence of the authenticity of his account. For instance, Daniel 3:1-6 reports

that Nebuchadnezzar set up a giant image for all the people to worship. Archaeologists

have found other evidence that this monarch sought to get his people more

involved in nationalistic and religious practices. Similarly, Daniel records

Nebuchadnezzar’s boastful attitude about his many construction projects.

(Daniel 4:30) Not until modern times have archaeologists confirmed that

Nebuchadnezzar was indeed behind a great deal of the building done in Babylon.

As to boastfulness—why, the man had his name stamped on the very bricks!

Daniel’s critics cannot explain how their supposed forger of Maccabean times

(167 BC-63 BC) could have known of such construction projects— some four

centuries after the fact and long before archaeologists brought them to light. The

book of Daniel also reveals some key differences between Babylonian and Medo-Persian

law. For example, under Babylonian law Daniel’s three companions were thrown

into a fiery furnace for refusing to obey the king’s command. Decades later,

Daniel was thrown into a pit of lions for refusing to obey a Persian law that

violated his conscience. (Daniel 3:6; 6:7-9) Some have tried to dismiss the

fiery furnace account as legend, but archaeologists have found an actual letter

from ancient Babylon that specifically mentions this form of punishment. To the

Medes and the Persians, however, fire was sacred. So they turned to other

vicious forms of punishment. Hence, the pit of lions comes as no surprise.

Another contrast emerges. Daniel shows that

Babylonian King Nebuchadnezzar could enact and change laws on a whim. King

Darius however could do nothing to change ‘the laws of the Medes and the

Persians’—even those he himself had enacted! (Daniel 2:5, 6, 24, 46-49; 3:10,

11, 29; 6:12-16)

Historian John C. Whitcomb writes: "Ancient

history substantiates this difference between Babylon, where the law was

subject to the king, and Medo-Persia, where the king was

subject to the law."

The thrilling account of Belshazzar’s feast,

which is recorded in Daniel chapter 5, is rich in detail. Apparently, it began

with lighthearted eating and plenty of drinking, for there are several

references to wine. (Daniel 5:1, 2, 4) In fact, relief carvings of similar

feasts show only wine being consumed. Evidently, then, wine was extremely

important at such festivities. Daniel also mentions that women were present at this

banquet—the king’s secondary wives and his concubines. (Daniel 5:3, 23)

Archaeology supports this detail of Babylonian custom. The notion of wives

joining men at a feast was objectionable to Jews and Greeks in the Maccabean

era (167 BC-63 BC). In view of such details, it seems almost incredible that

the Encyclopedia Britannica could describe the author of the book of Daniel as

having only a "sketchy and inaccurate" knowledge of the exilic (587

BC–538 BC) times. How could any forger of later centuries have been so

intimately familiar with ancient Babylonian and Persian customs? Remember, too,

that both empires had gone into decline long before the second century BC.

There were evidently no archaeologists back then; nor did the Jews of that time

pride themselves on knowledge of foreign cultures and history.

Only Daniel the prophet, an eyewitness of the

times and events he described, could have written the Bible chapter bearing his

name.

2. Countering the critics

arguments

The case of the missing monarch

Daniel wrote that Belshazzar, a "son"

of Nebuchadnezzar, was ruling as king in Babylon when the city was overthrown.

(Daniel 5:1, 11, 18, 22, 30)

Critics long assailed this point, for

Belshazzar’s name was nowhere to be found outside the Bible. Instead, ancient

historians identified Nabonidus, a successor to Nebuchadnezzar, as the last of

the Babylonian kings. Thus, in 1850, Ferdinand Hitzig said that Belshazzar was

obviously a figment of the writer’s imagination. But does not Hitzig’s opinion

strike you as a bit rash? After all, would the absence of any mention of this

king—especially in a period about which historical records were admittedly

scanty—really prove that he never existed? At any rate, in 1854 some small clay

cylinders were unearthed in the ruins of the ancient Babylonian city of Ur in

what is now southern Iraq. These cuneiform documents from King Nabonidus

included a prayer for "Bel-sar-ussur, my eldest son." Even critics

had to agree: This was the Belshazzar of the book of Daniel.

The Nabonidus Cylinder names King Nabonidus and his son Belshazzar

Yet, critics were not satisfied. "This

proves nothing," wrote one named H. F. Talbot. He charged that the son in

the inscription might have been a mere child, whereas Daniel presents him as a

reigning king. Just a year after Talbot’s remarks were published, though, more

cuneiform tablets were unearthed that referred to Belshazzar as having

secretaries and a household staff. No child, this! Finally, other tablets

clinched the matter, reporting that Nabonidus was away from Babylon for years

at a time.These tablets also showed that during these periods, he

"entrusted the kingship" of Babylon to his eldest son (Belshazzar).

At such times, Belshazzar was, in effect, king—a

coregent with his father. Still unsatisfied, some critics complain that the

Bible calls Belshazzar, not the son of Nabonidus, but the son of

Nebuchadnezzar. Some insist that Daniel does not even hint at the existence of

Nabonidus. However, both objections collapse upon examination.

Nabonidus, it seems, married the daughter of

Nebuchadnezzar. That would make Belshazzar the grandson of Nebuchadnezzar.

Neither the Hebrew nor the Aramaic language has words for

"grandfather" or "grandson"; "son of" can mean

"grandson of" or even "descendant of." (Compare Matthew

1:1.)

Further, the Bible account does allow for

Belshazzar to be identified as the son of Nabonidus. When terrified by the

ominous handwriting on the wall, the desperate Belshazzar offers the third

place in the kingdom to anyone who can decipher the words. (Daniel 5:7) Why

third and not second? This offer implies that the first and second places were

already occupied. In fact, they were—by Nabonidus and by his son, Belshazzar.

So Daniel’s mention of Belshazzar is not evidence of "badly garbled"

history. On the contrary, Daniel—although not writing a history of

Babylon—offers us a more detailed view of the Babylonian monarchy than such

ancient secular historians as Herodotus, Xenophon, and Berossus. Why was Daniel

able to record facts that they missed? Because he was there in Babylon. His

book is the work of an eyewitness, not of an impostor of later.

The Matter of Language

When the writing of the book of Daniel was

completed in about 536 BC it was written in the Hebrew and Aramaic languages,

with a few Greek and Persian words. Such a mixture of languages is unusual but

not unique in Scripture. The Bible book of Ezra too was written in Hebrew and

Aramaic. Yet, some critics insist that the writer of Daniel used these

languages in a way that proves he was writing at a date later than 536 BC One

critic is widely quoted as saying that the use of Greek words in Daniel demands

a late date of composition. He asserts that the Hebrew supports and the Aramaic

at least permits such a late date—even one as recent as in the second century

BC.

However, not all language scholars agree. Some authorities have said that

Daniel’s Hebrew is similar to that of Ezekiel and Ezra. As to Daniel’s use of

Aramaic, consider two documents found among the Dead Sea Scrolls. They too are

in Aramaic and date from the first and second centuries BC—not long after the

supposed forgery of Daniel. But scholars have noted a profound difference

between the Aramaic in these documents and that found in Daniel. Thus, some

suggest that the book of Daniel must be centuries older than its critics

assert.

What about the "problematic" Greek

words in Daniel?

Some of these have been discovered to be Persian,

not Greek at all! The only words still thought to be Greek are the names of

three musical instruments. Does the presence of these three words really demand

that Daniel be assigned a late date? No. Archaeologists have found that Greek

culture was influential centuries before Greece became a world power.

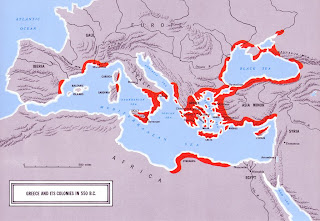

Greece and it's colonies in 550 BC - The most powerful civilisation in Europe at that time. Greece was clearly already a power and influential back than, before the Book of Daniel was completed by the prophet Daniel.

Furthermore, if the book of Daniel had been composed during the second century BC like critics claim, when Greek culture and language clearly was the dominate language and culture in the world and very pervading, would it contain only three Greek words? Hardly. It would likely contain far more. So the linguistic evidence really supports the authenticity of Daniel.

___________________________________________Back to Mainpage: